How do criminals move their dirty money? In financial services we’re taught about the methodical way it’s done. The three stages of money laundering are placement, layering and integration. Any wealth professional can tell you that in their sleep. Most investment houses won’t even let you touch a piece of work before you’ve successfully passed a couple of tests on the topic.

Discreet but perfectly legal

Even though the AML (Anti Money Laundering) online exam is arse-numbingly boring, normally put together by a well-meaning but IT-basic compliance person, the topic retains it’s thrilling edge. Images spring up of cocaine-laden Mexican cartels packing away lorryloads of damp dollar notes or hardened Dirty Harrys stashing hordes of blood diamonds stolen from Hatton Garden. I’m sure that happens once in a blue moon.

Yet, just over the road, somewhere like quiet Talstrasse in Zurich, suspicious money is squirrelled away every day. And it’s perfectly legal. This is done by peculiar little firms selling shelf companies.

Hiding money in shelf companies

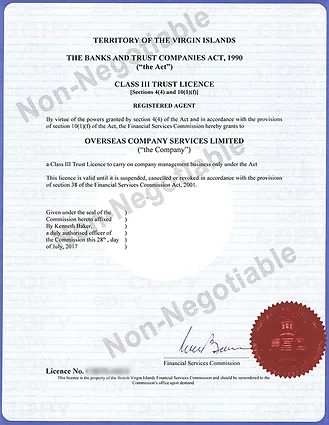

A shelf company is a “company” in legal terms but nothing else. When you buy it, you get a piece of paper with your name added as the director (or not even) and a red stamp. From there, you can put money into the company and hey presto… your money is no longer under your name.

You can buy things like property with your shelf company. You could even buy companies (you own) with your shelf company and then buy property. Or other investments, like shares, bonds… even art and vintage cars. (I guess this could count as legal “layering”, the second stage of money laundering).

In the UK, it’s estimated that 40,000 properties are owned this way. London’s Belgravia is like shelf company central.

Once someone buys the shelf company, it’s officially called a “shell company”. I guess because it’s a hollow vessel for money. But the terms are used interchangeably. Shelf, Shell… who cares… it’s a tax-free bank account basically.

Registering shelf companies in tax havens

All these shelf companies are usually registered in tax havens. I spent three traumatic months making shelf companies for a scary-yet-boring firm in Zurich, and I noted that the most popular destination was the British Virgin Islands. By a long way. Second to that would be Seychelles or Panama. And then occasionally you’d get one in Guernsey, Jersey, the Bahamas or Cyprus but not often. The firm I worked for stored copies of every shelf company, and it was an entire room packed to the rafters. That’s a lot of tax not being paid.

I would say that between three and twenty shelf companies got incorporated every day. Sometimes more than one for the same person. Often some for their kids and wives too.

It takes less than an afternoon

Trusts or “Corporate Administrative Services” (even the name is boring – I think it’s part of a sort of hide-in-plain-sight disguise) create shelf companies ahead of time. And then they quickly sell them to buyers. They literally sit on a shelf until someone buys one. That’s where the name comes from.

The whole process of handing a company over with all the correct documents takes less than an afternoon. Even I was trusted to do it as a brand new joiner. It’s super easy. You see that little red star stamp on the incorporation document? That was done in the office. You get a red wax thing, and a little press and bob’s your uncle. There’s an in-house lawyer signing things and a bunch of naïve people (like me) preparing paperwork. Easy-peasy-lemon-corruption.

“British-sounding” company names

I wasn’t there for long, but one of my main tasks was to think of company names. “British-sounding names” apparently was what everyone wanted. So, that’s what I did for the first few days. “Tudor Holdings Ltd”, “Primrose Cottage Management”, “Branson Estates”. That kind of thing. I filled up a few A4 sheets with suggestions. And they got made into hot-selling shelf companies.

In the years that followed, I felt very sick with myself about that. What I’d been a part of didn’t really click in my mind until I’d completed an investment management certificate in my mid-twenties. After that, I began to question what the firm actually did all day. And whether it was morally reprehensible.

Yet, it is perfectly legal – actually quite a respectable job. “Corporate Administrative Assistant” was my title.

Scandals and suspicious clients

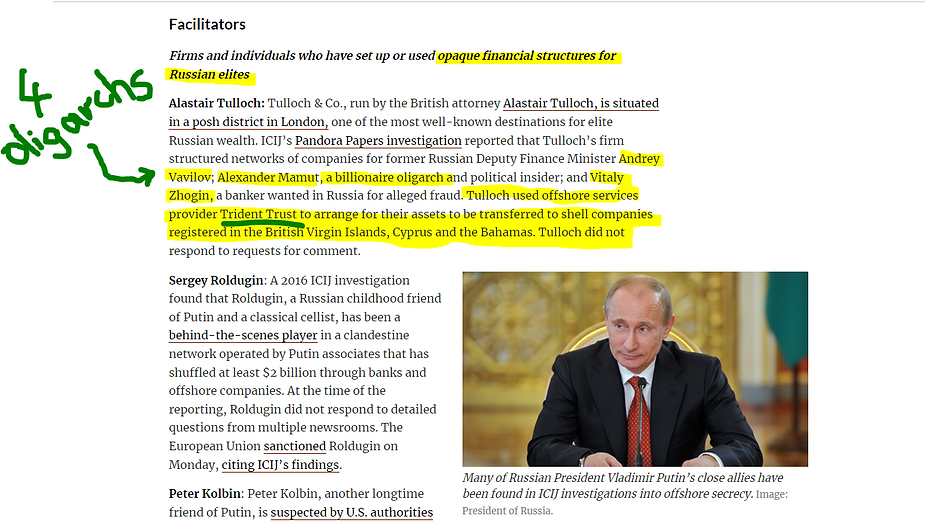

Every client I ever saw or created a shelf company for was an insanely wealthy Russian speaker. I mean multi-millions. Russian was spoken more in the office than English or Swiss German put together. Which does make you wonder where all of this mind-blowing wealth was coming from and why it had to be quietly packaged off to a shelf-company for a few years.

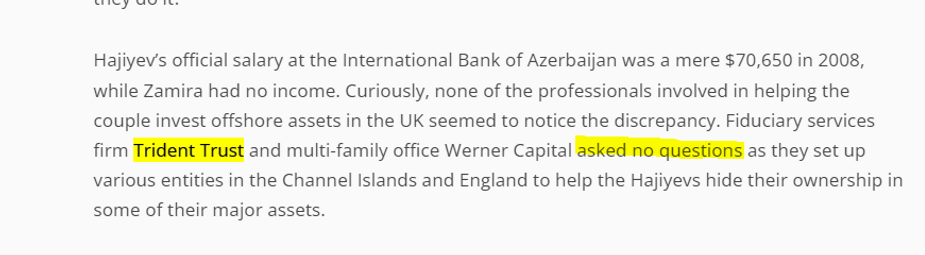

I should say that we did have to do checks on individuals. We had this database, where you would type in someone’s name, and it would flag them if they were dodgy. But I think the platform was quite lenient, because I remember typing in some names of people who I knew were registered bankrupts in the UK and nothing came up. Firms like my old one have since been accused of asking zero questions about the source of the money. And I can easily believe that.

Over the last years, there have been multiple scandals around oligarchs shifting money through the company I worked in. To be honest, I’m surprised there are not more.

Trust services and family offices

There are a great many of these small and boring “Trust Services” or “Corporate Services” around London and Zurich. Probably you can also find them left, right and centre in places like Guernsey, Jersey, Monaco and even Luxembourg too. Family offices is another classic.

Billions upon billions of dollars must be flowing through these little firms and into shelf companies. Not just for potential oligarchs. For all kinds of people trying to hide money or escape taxes.

Last year for example, the Pandora Papers were leaked. They exposed how law firms, family offices and trust services – including the one I worked for – enabled politicians, millionaires and artists hide vast fortunes linked to Spain in opaque off-shore companies. Including 46 Russian oligarchs.

During my brief time in the office, I didn’t really see any Spanish or Latin-sounding names. But it turns out that my firm was also heavily implicated in funnelling money for corrupt politicians and even celebrity musicians! I had no idea that Sharika and Real Madrid coach Carlo Ancelotti may have also been on the books!

No talking

My old office had the strangest policy I’ve ever encountered, “silence at the desks”. From 8.30am until 5.30pm we were not supposed to talk. I remember once I passed a post-it to my bestie and she laughed so hard that the whole office just looked up and stared at her. Without even a trace of a smile, she was coolly instructed to stand outside on the balcony until she could compose herself.

We were even forbidden from taking lunch breaks at the same time as our friends, and encouraged (forced) to eat alone. Looking back, I think that may have been to stop us finding out too much about the clients, as our roles were quite siloed.

The office was weird. Nobody could deny that. No talking. Clean desk at all times. Literally, I had to spray and wipe it down. Rigid timekeeping. And a boss who would shout like hell for literally no reason at some people, while petting others. I felt desperately sorry for my American colleague who was bullied by our boss relentlessly. When you have someone like that in charge, it makes it very difficult ask questions.

Regulation and transparency urgently needed

Since the 2008 financial crisis, there’s been a great push for transparency in global banks and wealth managers. With mixed results. But regulators have been onto them, and that’s an important step. Compliance has increased so much that the department is sometimes the largest in the whole bank. But that same vigour hasn’t really applied to the opaque world of family offices, trusts, and niche private equity.

These are firms that are raking in incredible sums of cash. One report shows that my old office charged £30,000 in “administrative” fees. With the sheer quantity of companies incorporated, they must’ve been making hundreds of thousands every day. (By the way, my salary was 65,000 Swiss Francs a year. Around £40,000 at the time. Less than two companies’ worth. I know that other colleagues were paid quite a lot less. Maybe because I’m British it added something to their image? My boss sometimes showed off to clients that I’m English, even though I’m Welsh).

Were we being used?

Something I think is quite important to note is that none of us in the scary-but-boring firm (as I recall) undertook any basic AML or Compliance tests. We just started work. That couldn’t be more different from the big banks.

On day one we were already making shelf companies. Like a little factory. I don’t think that any of us had any qualifications in finance either. I certainly didn’t. Nor my bestie. I’d freshly graduated with a law degree from Exeter, and was new to Zurich. And I remember that I was one of the only degree-holders. I don’t think any of us really knew much about the complex underbelly of shelf companies or what to look out for around money laundering.

A lot of us were also all young women (and all of us were women). I was 22. So was my bestie. Young, clueless and eager to please our volatile boss. Truth be told, today I feel a bit tricked about the work I did. I feel used. Because if I had really understood what was going on, I would never have taken that job. It’s a disturbing way to make a career. I believe that I was paid in dirty money and it makes me feel quite sick.

Maybe it’s time that people in the industry took a stand. I wish I had. Maybe I still can now. My days there ended after I got fired within three months for being a bad fit.

If my old bosses are reading this now, I still think you’re a pair of dickheads.